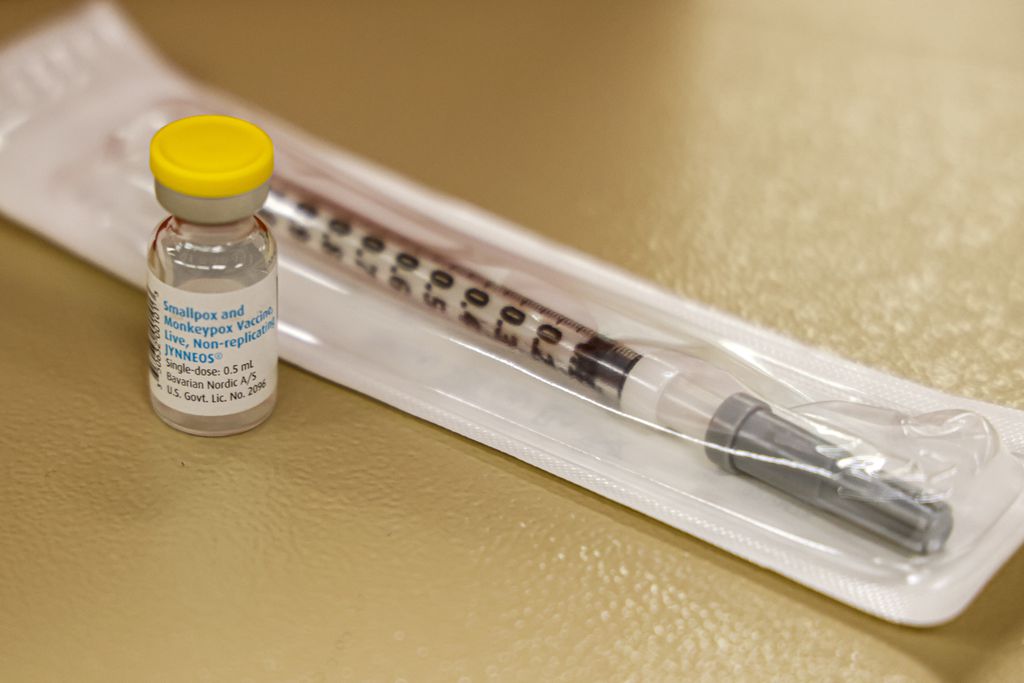

Among those who have received the monkeypox vaccine in Massachusetts, the state’s analysis shows, 11 percent were Hispanic and 5 percent were Black.NELL REDMOND/AP/FILE

By Felice J. Freyer Globe Staff,Updated September 10, 2022, 4:21 p.m.

The monkeypox outbreak appears to be waning in Massachusetts, as in the rest of the country, but new data reveal stark ethnic and racial disparities in who is getting sick and who is getting vaccinated.

Among reported monkeypox cases in Massachusetts, 29 percent werein Hispanic people and 15 percent in Black people, according to a reportlastweek from the state Department of Public Health.

But among those who have received the vaccine, the state’s analysis shows, only 11 percent were Hispanic and only 5 percent were Black.

The state also reported a decline in cases — and a Provincetown clinic hasn’t seen a new monkeypox case in two weeks. But Provincetown has few Black and Hispanic residents, and those groups are bearing a high burden of monkeypox illnesses.

“Men of color are disproportionately affected by this,” said Dr. Jacob Lazarus, an infectious disease physician at Massachusetts General Hospital. “Like we saw with COVID, they have less access [to vaccines] for many reasons. … We need to do a better job of reaching out to everybody.”

The state Department of Public Health has several efforts in the works to address the disparity, a spokesperson said Friday. They include plans to set up mobile vaccine sites at clubs and events “where Latino and Black men who have sex with men socialize and feel safe,” increased opportunities for walk-in vaccinations, informational ads on dating sites, and paid social media targeted to people of color and in multiple languages.

Although anyone can contract monkeypox, the current outbreak is spreading in communities of men who have sex with men. Transmission occurs primarily through direct skin-to-skin contact with an infected person with lesions. Monkeypox causes two to four weeks of illness that can be severe, but in the current US outbreak, only two deaths, in Texas and California, occurred in people infected with monkeypox.

The Massachusetts numbers echo national data showing that the majority of new monkeypox cases are among Black and Hispanic people, even as the majority of vaccines are going to whites.

Federal officials, while noting these disparities, also expressed hope that the case numbers would continue their apparently downward trend. More than 21,000 cases — including 347 in Massachusetts — have been reported nationwide since May.

But no one is saying that the outbreak is over.

“There’s still a lot of unknowns,” said Carl Sciortino, executive vice president of external relations at Fenway Health. “Clearly the numbers look better. That’s a positive for sure. But as we’ve seen with COVID — things go down, things go up.”

On Thursday, state health officials reported 30 new monkeypox cases identified between Sept. 1 and Sept. 7. That’s down from 37 in each of the previous two weeks and well below the peak of 45 new cases in the first week of August.

Health care providers who serve people at risk of monkeypox say the numbers jibe with their experience.

Outer Cape Health Services, which treats a large LGBTQ population in Provincetown, hasn’t seen a single new monkeypox case in about two weeks, after diagnosing two dozen cases and administering 4,500 first and second doses since the outbreak started, said Dr. Andrew Jorgensen, the agency’s chief medical officer.

“Here on the Cape we are seeing a decrease in cases,” he said. “It’s hard to know whether it’s because of the vaccine or because we have reached a new phase in our seasonality.”

“We’re very hopeful that because there has been some success in delivering the vaccine to the highest risk individuals that we won’t have to worry about this in a few months,” Jorgensen said. “Like all outbreaks, only time will tell.”

At Mass. General, Lazarus said, “We’re still seeing cases. It feels like there are fewer of them.”

The most important factor driving cases down, he said, is changes in sexual behavior by those at risk. In a recent CDC survey of men who have sex with men, half said they had reduced their number of sexual partners, one-time sexual encounters, and use of dating apps to avoid monkeypox infection.

The vaccine is also making a difference, Lazarus said, with some 461,000 doses distributed nationally and 20,000 in Massachusetts. Mass. General has administered 3,200 shots. In the past two weeks, he said, 80 percent of those shots have been second doses, increasing the number of people fully vaccinated against monkeypox.

Fenway Health is also seeing fewer monkeypox cases, Sciortino said. “There’s still a consistently high demand for vaccines. We’re able to meet the demand, filling all the slots we have,” he said.

Because the supply of vaccine remains limited, the CDC guidelines allow it only for people who are known contacts of a person with monkeypox, or who might be at risk because they had multiple sexual partners in a region where the virus is spreading. “Having to disclose sexual activity has been a barrier for a lot of folks,” Sciortino said. “It feels very intrusive.” On the flip side, he added, “We also know people are lying and saying whatever they need to say to get the vaccine.”

Sciortino said Fenway’s data show ethnic and racial disparities similar to those in the state report. “There’s a legitimate reason for medical mistrust in BIPOC communities — lots of historic and current reasons,” he said. But other than that, he’s not sure why fewer Black and Hispanic men are coming in to get vaccinated.

Fenway has started direct outreach to its Black and Hispanic patients, he said; case managers are calling, e-mailing, and texting with information about monkeypox and how to schedule a vaccine appointment.

“We’ve known since day one we need to do more aggressive, targeted outreach,” Sciortino said. But throughout the state, the first phase of the vaccine rollout focused on getting the message out broadly, to as many people as possible, rather than focusing on “communities that have lots of reasons not to trust medical institutions,” he said.

“And now we’re playing catch-up,” Sciortino said. “We have work to do.”

Felice J. Freyer can be reached at felice.freyer@globe.com. Follow her on Twitter @felicejfreyer.